Ius sine lege

::Pages::

Home

Contact

Books

Texts

Teaching

Links

By the way

::Introductions::

Computer engineer?

My son's website

![]()

Last update

2004-12-12

(C) 2004

Frank van Dun

Gent, België

Journal des economistes et des études humaines VI, 4, 1996, 555 - 579

The Lawful and the legal

Abstract

Abstract. This paper presents an etymological approach to the confusing language of law and rights. It attempts to uncover the archetypical situations and relationships that appear to have been the original referents of words such as 'law' and 'rights', 'legal' and 'just', as well as other words that are indispensable in discourses about law and justice: 'freedom', 'equality', 'peace', 'authority', 'society' and others. The concepts of the lawful and the legal can be clearly distinguished. The distinction between them sheds an interesting light, not only on the lawyer's conception of law, but also on the old controversy over natural law. From the analysis there emerges a distinctly liberal conception of social order as well as a a naturalistic, non-normative conception of natural law, with no metaphysical or theological connotations of a "higher law". The elements uncovered by the analysis provide a coherent scheme of law that can serve as the basis for a non-deontic, rights-based logic of law.

The Lawful and the legal

Familiar linguistic data indicate that the language of law and rights refers in a confusing way to a variety of very different ideas, and ultimately to a variety of very different situations, relationships and activities.

To discover these differences is the object of the ancient science of etymology, the "study of the real or true state of things", i.e. the attempt to uncover the real differences in the things themselves, or in the significance of things for human needs and aspirations. In this paper I shall review the etymological evidence for the thesis that the lawful (what answers to law or justice) and the legal (what answers to the enacted laws) are not just distinct concepts, but belong to categorically different perspectives on the social aspect of human existence. As we disentangle the concepts of the lawful and the legal, that are nowadays usually assimilated, or even considered identical, we discover a recognisably "liberal" picture of society as the peaceful order of relations among separate but (in a definite sense of the word) equal human beings, each of them a naturally, i.e. physically, finite person with his or her own equally finite, physically delimited sphere of being and work, i.e. property. In other words, we discover not just that there is a difference between the lawful and the legal, but also the distinctive characteristic or principle of law ("freedom among equals") and of justice ("to treat others as one's likes").Before we begin our etymological enterprise, we shall consider the equation of the concepts of the lawful and the legal, first in the way lawyers commonly use the word 'law', and then in the light of the dominant positivistic paradigm of thinking about law. Because legal positivism has historically defined itself in opposition to theories of natural law, I shall comment on the nature of that opposition. Positivism rests to some extent on a legitimate critique of a number of historically important theories of natural law, but it has failed to grasp the extent to which these theories of natural law have betrayed the basically naturalistic concern of natural law. We shall see, however, that our etymological investigation reveals a viable naturalistic conception of natural law that is immune to the positivists' critique.

Legal positivism And Natural law

The doctrines of legal positivism have provided the law schools with the comforting notion that law is to be found in the things lawyers know and practise. Consequently, to study these things, to familiarise oneself with them, to acquire the necessary skills to use and apply them in a wide range of real life (or: court) situations, should suffice as the proper aims of an education in the law. It is little wonder, that the "education in the law" these schools provide resembles nothing so much as an initiation in the rites and customs of a particular profession, its dogmas, doctrines and prejudices, especially concerning the so-called "sources of law": legislative, judicial and administrative rulings, treaties, and the main currents of opinion among the members of the profession. Positivism has rationalised the idea that "law" has its source in the decisions of designated political and professional authorities. By equating the lawful with the legal, it has helped to push the study and practice of law away from considerations of justice into a mere expertise in legality.

It is a common opinion among lawyers, that law is a fairly definite something at a given time and place, but may and is likely to be different at different times or places. Some go so far as to say that, conceptually, law can be anything. As one textbook puts it: "It is impossible to define [law] in a way that does justice to reality.... Almost all jurists who give a definition of law, give a different one. This is, at least in part, to be explained by the fact that law has many aspects, many forms, and also by its majesty or grandeur." Apparently, law defies definition. Law students should realise that the definitions of the theorists and philosophers never capture more than one or a few aspects or forms of law. Lawyers, who deal with all the aspects and forms of the law, should know that the legal material is a turbulent mass of diffuse, heterogeneous, often fleeting and sometimes contradictory things. However, in the same chapter of the same book, we can also read this: "Thus, law is society, human existence, or rather that particular aspect of it that we call social order." If this means that law is a principle of society, or a principle of social order, it is a statement with which few people would disagree. "L'ordre social est un droit sacré, qui sert de base à tous les autres". With these words, Jean-Jacques Rousseau expressed what is really the traditional conception of law as well as the reason for the esteem in which it is traditionally held.

Clearly, the lawyers' attitude towards law is ambiguous. On the one hand, when lawyers want to justify their claims to authority and prestige, they adopt the language of natural law, with many references to "principles of social order or justice". On the other hand, they show no inclination whatsoever to make the study of social order or justice the basis of their activities as students or practicioners of the law. In fact, they are prone to accept the positivists' repudiation of the very notion of natural law as irrelevant, or even utterly "unscientific" and "ideological". Positivism justifies this repudiation of natural law inter alia with the argument that science should be value-free, and that the lawyers' science can be value-free only if it sticks to the "law as it is", without concern for "what the law ought to be". But "the law as it is" is simply what, according to the general consensus among lawyers, currently is or embodies "law". From this perspective, natural law should be relegated to the domain of extra-legal speculation about what law ought to be: natural law exists only as mere opinion, it does not exist as a fact, it is not law.

It is easy to see that the positivistic critique of the notion of natural law rests on a misconception. The basic tenet of any doctrine of natural law is that the existence of law is independent of opinions about what law is or ought to be. From the perspective of natural law theory, the maxim that a science of law should consider only "law as it is, and not what one might believe ought to be law" is as self-evident as the maxim that science should study "the world as it is, and not as one might believe it ought to be". Natural law is not a human fabrication; it is not something to which the distinction between ought and ought not applies. On the other hand, what is called 'positive law' is a product of human activity, of human interests and opinions. Surely, the natural law theorists will say, there is nothing scientific about restricting one's study of human opinions to determining what they are, without any attempt to critically evaluate their truth value. Every science aims to go beyond the opinions on its subject-matter, even those currently held by its own practicioners, to the truth of the matter. If, as the positivists claim, law is "positive law" and "positive law" reflects human opinions, then the proper scientific attitude is to check whether the opinions that make up the positive law agree with natural law. From the natural law perspective, then, legal positivism amounts to a refusal to make law the subject of a critical scientific inquiry.

The positivists may object that the opinions that make up the law as they define it are not opinions about matters of fact, but about what ought or ought not to be the case, about what is good or bad, better or worse. The point of the objection is, of course, that such opinions about norms and values may not be the sort of opinions of which we can sensibly ask whether they are true or not; or that, if there is some sense in asking this, we have no agreed on procedure for deciding such issues other than the appeal to effective authority. But this objection misses the point. Natural law theory, properly understood, is not some sort of normative moral theory. It does not seek to make moral judgements. It seeks to identify the principles of social order, to judge human actions as either lawful or unlawful, depending on their relation to such principles. The question "What is law?" is logically distinct from, and prior to, the question "Should we live according to law?".

It is true, that some moralists have tried to represent their own particular moral ideals as principles of social order, often to justify attempts to legislate and enforce their programs of "moral reform". These attempts to read particular moral ideals into the principles of social order have in the end tended to discredit the paradigm of natural law by shifting the focus of attention from the objective conditions of society to the significantly different concept of "the good or perfect society". This shift originated with the reaction of Plato and Aristotle against the historical and naturalistic approaches to social order of the fifth century thinkers and philosophers of Athen's Golden Age: the Sophists, and naturalists such as Democritus. Visions of the perfect society underlie the false conception of natural law (ius naturale) as a system of natural laws (leges naturales). They present law as essentially normative, an ought that defies reduction to any material condition of mere existence. Law, in this sense, provides a solution for every problem, and points the way towards excellence and perfection in every aspect of life. As such, laws can only be expressed in statements about what people should or should not be or do. Thus, natural laws appear to have the same form as moral rules and also as laws issued by those in authority. This makes natural law a "higher law", one that stands above, and serves as a model for, the directives and commands, the rules and regulations of the political authorities as well as the mores of the people. Natural law, in short, is made to appear as an ideal legal system, with the distinguishing characteristic that its validity in no way depends upon its being enacted as positive law. However, the turn towards metaphysics and moralism did not obliterate all traces of a naturalistic investigation of social order. Aristotle did not repudiate such investigation; he merely tried to render it harmless to his own moralistic preoccupations by going beyond physics (the study of nature) to metaphysics (the attempt to fit nature into a teleology that discloses the ultimate meaning or direction of the world). It is instructive to see how Thomas Aquinas at once proclaims the directive powers of natural law with respect to every aspect of life, and concedes that it would not be practical or wise for the human legislator to try to enforce all the presciptions of natural law:

"[Because] law regards the common welfare...there is no virtue whose practice the law may not prescribe." [However,] "human law is enacted on behalf of the mass of men, most of whom are very imperfect as far as the virtues are concerned. This is why law does not forbid every vice which a man of virtue would not commit, but only the more serious vices which even the multitude can avoid. These are the vices that do harm to others, the vices that would destroy human society if they were not prohibited: murder, theft, and other vices of this kind, which the human law prohibits."

Saint Thomas refers to the naturalistic notion of law as the condition of social existence only indirectly, and then only by way of a merely pragmatic concession in an otherwise idealistic frame-work of natural laws that prescribe all the virtues. The same attitude prevails in the writings on natural law of the later Scholastics, and also of the rationalistic natural law theories of the seventeenth century. We can understand why the positivists have always focussed their attention on this normative conception of natural law as a "higher law". Apart from its metaphysical trappings, it exactly matches their own conception of law. But the "higher law" theory gets mired in all the endless and undecidable controversies about "the truth of norms", their existence and grounds of validity. It can hardly escape the fate of becoming no more than a rhetorical device for dressing up any political or legislative programme with the prestige of philosophy or religion. Positivism has tended to relate the "natural law" exclusively to efforts to use metaphysical and theological schemata to read some particular moralistic conception of "the good society" into the natural order of things. It has failed to grasp that such efforts confound the natural with the meta-natural or the supernatural. Early modern positivists set out to provide a naturalistic foundation for the normative conception of law, without relying on the assumption that every valid law prescribes behaviour that is already prescribed "by nature". Arguing from the sceptical premises that there is no way of knowing the true principles of "the good society", and from the conviction that no society can exist when everybody acts on his or her own beliefs, the founding fathers of modern positivism arrived at the conclusion, that the basic condition of social life is that people do not act on their own judgements. Thus Hobbes argued that, as no society is possible when we all do as we please, society is possible only when we all do what one of us wills. Moreover, since we are all naturally inclined to act on our own judgements, society cannot arise "by nature". Society is an artificial construction; it requires an architect, a sovereign, i.e. an individual monarch or a monarchical assembly that acts "as one man", capable of imposing his will on all. For Hobbes, the existence in this form of an irresistible "power to keep everyone in awe" is the condition that makes society possible. Except for this fundamental law of social existence, law is what the sovereign as such wills. Again, the lawful and the legal coïncide, only this time they do not do so only if human legislation accords in full detail with the presciptions of nature; they coïncide because no society could possibly exist if it were not organised by the legislative activity of rulers. It seems, then, that positivism holds that the lawful and the legal are necessarily identical, while classical [metaphysical] natural law theory only maintains that they should be identical. However, both approaches seem to agree, that law is essentially normative and that every aspect of human life and action could conceivably and lawfully be prescribed by human laws.

The outcome of the discussion so far is a dilemma: from the point of view of classical natural law theory a strong case can be made against legal positivism; but the positivists have an equally strong case against the classical idea of natural law. We should question the positivists' thesis of the equation of the lawful and the legal - or, as some positivists have expressed it, of law and the state - because there seems to be no inconsistency in the idea of a state without law or justice, whereas the idea of a state without a legal system of some sort most certainly is inconsistent. Also, there is no inconsistency in saying that some law or collection of laws has no connection with justice; but it would be a contradiction in terms to declare that there is no logical connection between law and justice. On the other hand, the posivists are assuredly right in ridiculing the claim of classical natural rights theory, that "nature", on account of its inherent telos or by divine providence, prescribes for us in minute detail what we ought to do or strive for, even if the practical import of this claim is usually weakened by conceding, that human laws should not presume to enforce everything the natural laws prescribe.

The etymology of law and right

The previous section left us in a dilemma. Is there an escape out of this dilemma? I think there is one, if we are willing to divest the notion of natural law of its metaphysical garments. This is where we can employ the resources of etymology in an endeavour to discover "the real or true state of things", i.e. the original meanings of terms which we may have lost sight of in the furor of the interminable squabbles among axe-grinding theorists. The search here is for a naturalistic conception of natural law, one that provides an unambiguous criterion for judging the lawfulness of actions, including legislative actions, without necessitating any recourse to "knowledge of metaphysical things", and without having to fall back on mere knowledge of the commands of the sovereign or his agents.

My starting point will be, that law as justice ("Recht", "Droit") seems to denote a horizontal relationship between equals, whereas law as the measure of legality ("wet", "Gesetz", "loi") seems to denote a vertical relationship within a hierarchy, between a superior law-giver or legislator and one or more inferiors or subjects. Let us, then, take a look at the concept of equality and its relation to the concept of justice.

In some languages, for example in Dutch and German, the word for equality is one that in a literal translation would be rendered in English as 'likeness': 'gelijkheid', 'Gleichheit'. The etymological root is 'like' ('lijk', 'leich') which means body, or physical shape. Thus, one's likes are those who are of similar shape, or those who have the same sort of body. There is no connection here with the Latin 'aequus' or 'aequalitas', which suggest not "likeness", "similarity", "sameness" or "being of the same sort", but rather "having the same measure". In a literal sense, the concept of aequalitas does not apply to human beings as such, but only to particular measures of shape, rank, ambition, ability or excellence: two persons cannot be equal as such, but they may be of equal height or equally good at doing something. Even if two persons were found to be equal in all respects, we should qualify their equality as an accidental and temporary condition. On the other hand, likeness or similarity is the outstanding characteristic of all human beings. In fact, it is only in their likeness or humanity that people are equal. However, this is an extremely abstract sort of equality. It adds nothing to the real or natural or objective likeness of all human beings, and it should not divert attention away from the fact that apart from their common humanity all people are different in many ways, and unequal with respect to many measures of shape, rank, ability or whatever.

The distinction between equality and likeness or similarity is of the utmost importance for the logic of justice. For most people "justice" and "equality" are inseparable. But there is a world of difference between justice-as-aequalitas and justice-as-similitudo. It is often said, that the fundamental requirement of justice is equal treatment of all. Taken literally, this is a requirement no one can possibly meet, and no one will appreciate. There is no way in which one can treat oneself as one can treat others, and no occasion on which one can meet out the same treatment to all others. Distributive equality applies, if at all, only to a well-defined, closed group, when all its members stand in the same relationship to the same distributive agent (the parent and his or her children, the teacher and his or her pupils, the commanding officer and his troops, the hostess and her guests, and so on) - and even so it presupposes the inequality of the distributor with respect to those in his care. In complex situations distributive equality merely disregards the inequalities that, by way of specialisation and the division of labour and knowledge, give rise to all the advantages of cooperation and co-ordination.

It is precisely because "equal treatment" in complex situations is an absurd requirement, that Aristotle found it necessary to add the amendment, that distributive justice requires that equals be treated equally, but unequals unequally. The whole point of distributive justice would be lost, if it did not serve to perpetuate the right sorts of inequality. And the point of distributive justice was for Aristotle essentially political: to make sure that the best, and only the best, rule, and that they perpetuate the particular morality or way of life of the community. Who are the best? They are those who within their community are considered the most eminent representatives of the community's way of life: its traditional "elite". Aristotle knew very well, that to apply the concept of distributive justice the rulers should be able to measure virtue; he also knew, that to measure virtue the rulers should always and continually keep the ruled under close "moral investigation" to determine the degree of their "political correctness or defects". These consequences did not bother him in the least. The whole of his political thought was framed by his vision of the polis as a small, self-sufficient community ruled by a political elite.

None of these complications arise with the concept of commutative justice, which we can express as the requirement that one treat all others as what they are, namely one's likes, and not, say, as one would treat an animal, plant, or inanimate object. This requirement can of course be phrased in terms of equality, e.g. as the requirement that every one should accord all others equal respect, or that one should recognise in all one does that all others are equally human. But again nothing is added by using the language of equality rather than that of likeness or similarity, except the risk of confusing "equal justice" with "equal treatment". Equal justice is achieved by doing injustice to no one, i.e. by treating others as one's likes; equal treatment can only be achieved by not doing anything.

With equality-as-similitudo we find an idea of justice that immediately brings into focus the idea of freedom. From an etymological point of view, 'freedom' is quite different from 'liberty'. The latter word is obviously derived from the Latin 'libertas', and refers to the status of a full member of some social unit (originally, a family or tribe). 'Libertas' is in fact the status of the liberi, i.e. the children, considered not as babies or young people, but as direct descendants. The same meaning attaches to the Greek 'eleutheria' (liberty), which is derived from a verb meaning 'to come'. Eleutheria, like libertas, is the status of "those who come later". In Dutch this meaning is rendered litterally by the word 'nakomeling' (one who comes later). Liberty points to a birthright, an inherited status, or to the status of one who has been adopted as a full member of the family or tribe. As a political term, 'liberty' suggest full membership in a political society, and points to notions such as nationality and citizenship.

Etymologists trace the origin of the word 'free' to an old Indian word 'priya' meaning: the self, or one's own, and by extension: what is part of, or related to, or like, oneself, or even: what one likes, or loves, or holds dear. Latin seems to have transformed 'priya' into 'privus' (one's own, what exists on its own or independently, free, separate, particular), 'privare' (to set free, to restore one's independence), and 'privatus' (one's own, personal, not belonging to the ruler or the state, private). The picture that emerges from these linguistic considerations is clearly focussed on the person and his or her property, not on some conventional status within a well-defined social unit. Political society - which in Aristotle's view, is unified by a constitution (a "moral" convention), and not by the ties of kinship that define the family and the tribal village - may have forged a link between freedom and liberty, but this should not obscure the fundamental distinction. Logically speaking, freedom may well be a ground for claiming liberty under the constitution, but even if a constitution denies the status of liberty to a free person, it does not thereby automatically deprive him of his freedom. Conversely, if a constitutional convention grants liberty to a person, it does not automatically make him more free than he was before. The grant of liberty gives him full membership and status in the constituted political organisation, and nothing more. Freedom belongs to the natural human being, liberty to a role player, a functionary in an organisation. In modern terms, we might say, that liberty belongs to the "public sphere" (i.e. to one's involvement with the business of the state), while freedom belongs to the "private sphere" where people meet one another as free natural persons with full responsibility for their own actions, and not as legal or fictional persons ("citizens") who are likely to explain and justify their actions in terms of legally or constitutionally conferred powers and privileges.

Thus, free, in the original sense of the word, is one who exists by his or her own efforts, one who is independently active, "his own man" or who lives "with a mind of her own". The proper context for the application of the word 'free' is the context of human interaction, where 'freedom' denotes leading one's own life, or making one's own decisions. This freedom is a correlation of likeness or equality-as-similitudo, but can hardly be reconciled with aequalitas. Likeness, as noted before, does not make one person the measure of another: it is not concerned with excellence in any respect. Also, to say that all people are alike does no violence to the fact that people are separate beings. Whether we are discussing the human person as a real physical entity (the human body) or as a source of physical activity (movement, emotions, thought), we always run into the inescapable fact of the separateness of persons: my body is nobody else's, my actions or deeds, my feelings and thoughts, are as a matter of fact my own, and this is true not only for me and mine, but also for you and yours, her and hers, and so on and on. My existence is and remains forever separate from your existence. We may say that freedom is a reality (one's own being, an inescapable fact beyond the reach of choice) as well as an activity (one's own work, Dutch: 'werkelijkheid', German: 'Wirklichkeit'). Real freedom (i.e. freedom as reality) is an inescapable fact of life: a person is free, and remains free until he dies; to destroy a person's real freedom one has to destroy the person. However, organic freedom (i.e. freedom as work) is contingent and vulnerable. All sorts of circumstances can prevent a person from doing his work, but only when the hindrance comes from within the proper sphere of freedom - that is to say: when it is the work of others - is it a violation of the condition of equality-as-likeness, i.e. of [commutative] justice. Such a violation of a person's freedom is traditionally and properly identified as an infringement of his right.

Organic freedom is indeed the substance of [subjective] right, as we shall see. Here we should note only that the word 'right' is nowadays understood mainly as referring to elements in a real or ideal legal system. Not surprisingly, it has acquired excessively normative overtones: a right is what the law says, or ought to say, a person, animal, plant, or whatever, should be given or allowed to have or do. It has lost virtually all descriptive content. Nevertheless, it is an indispensable word. In its original meaning it points to a very basic aspect of human life. Like the Dutch and the German 'Recht', the French 'droit' and the Italian 'diritto', 'right' reminds us of the Latin '[di]rectum', from '[di]regere', to make straight, or erect, and by extension of meaning: measure, regulate, rule, control, direct, manage, govern. The one who does the straightening, erecting, measuring, ruling or governing, is the rex (usually but misleadingly translated as 'king'), that which is under his control is his rectum - it is his right. The word 'right', when shorn of the current overgrowth of legal and normative meanings, evokes the drama of the struggle against an hostile environment; it conjures up an image of force and violent activity, of using physical power, manipulating things and subjugating people. Might gives right.

We may well ask how this extremely physical concept of right-as-might can be connected with justice. As we use the words 'right', 'recht', 'droit', 'diritto' now, the original meaning has almost completely vanished. The focus has shifted to the concept corresponding to the Latin 'ius'. In its original meaning 'ius' (plural: 'iura') stood for "a bond" or "a connection", but with little or no physical connotations. A ius originates in solemn speech ('iurare', to swear, to speak in a manner that reveals commitment and obligation). As such a ius is a logical or rational, i.e. a symbolic, hence social or moral bond. When the speech is reciprocal, the result is an agreement or contract among equals, an association. Ius connotes commitment and obligation, but also equality in the sense of likeness. By speaking to another, and waiting for his answer, by committing oneself towards him and waiting for him to commit himself, one treats him as one's like. It should be clear, that a ius implies, that the persons involved are mutually independent speakers. If one of them is a right, or within the right, of the other, there is presumably no ius between them. This presumption may be defeasible, but it cannot be dismissed out of hand, since one person's speech acts may also be controlled by the other, if the former is under the control of the latter. A ius, in short, stands in stark contrast to right-as-might. It creates no physical bond (or yoke) that serves to control or govern another as if he were an animal to be tamed and steered. Instead it creates a bond of an entirely different kind, a covenant that respects his likeness and leaves his freedom intact. The common idea of a bond links the notions of ius and right-as-might, but the different natures of the bonds, logical in the one case, physical in the other, are too obvious to ignore. Even if we disregard the aspect of physical force and violence in the practice of ruling (regnum), we should not overlook the difference between speech by which one obligates oneself (swearing, promising) and speech by which one obliges others (commanding).

The Romans also used the word 'ius' in a sense in which it cannot be put in the plural. Ius, for them, was was not just "a bond", but also "the social bond", the very existence of society, or its essential pattern. Conceptually, objective ius appears as the logical ground of specific iura, because these only express a commitment to act in accordance with objective ius. In Dutch, we refer to objective ius as "objectief recht", but also, and very appropriately, as "wet" (nowadays "[a] law", but originally: "what is known" or "what is common knowledge"). The English word 'law' in fact also referred originally to that which could be known by all, to the general order of things. It derives from 'laeg' (literally: the lay-out or order of things).

From an etymological point of view, 'right' and its continental equivalents are clearly unfortunate translations of 'ius'. We should also recognise that the original meaning of the Dutch 'wet' has been completely lost, at least in the discourse of lawyers and jurists. In English 'law' is used as often to refer to a legal system (or to its constituent elements, the laws promulgated or invoked by the law-makers) as to the principles of social order as such. On the other hand, we can easily see that the original meaning of 'right' and the new meanings of 'wet' and 'law' are very similar to the meaning of the Latin 'lex' (a law, plural: 'leges'). There is the same suggestion of a hierarchical or vertical relation between one who commands or compels and those who are commanded or compelled. A lex, for the Romans, was a decision of the highest public authorities (in particular the comitia) that binds their subjects. Lex stood in clear opposition to ius, the latter being a source of obligation either because of the nature of things, or because of the solemn or sworn agreement of those involved. The word 'lex' is traced back to 'dilectus', the raising of an army; its original meaning was: a public proclamation ordering the male population to do military service. It is related to the verb 'legere' (participle: 'lectum'), which means to collect, to pick up, even to steal. There is a clear reference here to the formation of a military organisation, and to giving orders, ruling, and, generally, to using and manipulating people in the pursuit of particular ends. A lex, then, denotes power over human beings, in the same way that regere or diregere denotes power over things in general.

Perhaps the positivistic current in thinking about law harks back to the original idea of right-as-might, and to its application in the form of leges to human material. This would explain its fascination with the phenomena of power and its almost total neglect of questions of ius and iustitia. There is, however, a straightforward way to harmonise the original meanings of 'right' and 'ius'. We only have to restrict the meaning of 'right' to the government or management of one's own work. In the same way, we can harmonise the concepts of ius and lex, if we restrict the application of lex to a person's command over his own property. With these restrictions, the physical activity that is a characteristic of right-as-might as well as of lex remains intact, but it is right or lawful only if it stays within the bounds of ius or justice. From the naturalistic perspective of natural law, the bounds of justice are nothing else than the real and organic boundaries of every person as a physical and acting or working entity. Specifically, ius implies that action across these boundaries must be based on, or sanctioned by, the agreement of those who are materially affected by it. In this sense, organic freedom as defined earlier is the source of right if, and only if, in exercising it one does not fail to deal with others as one's likes.

The conception of property as the product of one's organic freedom within the bounds of justice is familiar to all students of political thought. It corresponds to Locke's assertion that the property of an object originally belongs to its maker. Thus, the original title of property is auctoritas, the quality of being an auctor. 'Auctoritas' derives from the verb 'augere', which means "to grow [something]", and also "to improve, augment, produce, make, create, or found". Auctoritas is the original ground of lawful possession: what the auctor produces is, in an obvious sense, his - it is by or of him. This makes him solely responsible, answerable and liable for it, for what one produces cannot answer for itself, and, having no independent status in law, cannot be held liable. In this sense, the auctor guarantees what he produces. While we are nowadays inclined to view authority as perhaps primarily a direct vertical political relationship between one person who wields authority and another who is subject to it, in its original sense authority exists between a person and his work. In that sense, it applies to an interpersonal relationship only indirectly, as when one person who uses the property of another should concede the latter's authority over it.

Having authority over something is often confused with having a say over it. E.g. in Dutch, 'authority' is often translated as 'gezag' or 'zeggenschap' (literally: say, but also command, jurisdiction), although these words properly apply only to a relationship between persons. Ironically, to say in Dutch or German that something belongs to a person one should say that it listens to him ('toebehoren', 'zugehören'), or that it obeys him. In these translations, the original idea of auctoritas is lost and replaced by the idea of a relationship between master and subject. In this respect, they remind us of the extravagant conception of property proposed by Aristotle in Politics, where he claims that, properly speaking, only articles of direct consumption (food, clothing, a bed) and slaves can be property. The characteristic of property, for Aristotle, is that it is immediately useful to its owner. Articles of consumption are property because they yield their utility immediately in the use we make of them; and slaves are property because they are means of action (or life) that are serviceable without requiring any work on the part of the master, "whose will they obey or anticipate". Aristotle also considered a slave as "being better off when under the rule of a master... [because] he participates in reason enough to apprehend, but not to possess it". Thus, Aristotle cunningly suggests that owning slaves rests on auctoritas: the master "improves" the slave, who thereby becomes "a part of the master, and wholly belongs to him". For the same reason that slaves are property, tools, i.e. "means of production", are not property in Aristotle's sense. They belong to the banausic sphere of manual and wage labour, which, in the philosopher's appreciation, is a sort of "limited slavery". In this manner, while paying lip-service to the naturalistic conception of property as resting on auctoritas, Aristotle assimilated owning property to the rule of man over man, and at one and the same time justified the regulation of the trades by legislation as well as the legal inviolability of the ownership of slaves. Clearly, whether due to the influence of Aristotle or not, a lot of modern legal thinking about property fits nicely into the Aristotelian pattern: apart from an individual's claims to what he needs for direct consumption, only the state's claims to obedience are considered to be "inviolable property"; all other claims are subject to legislative regulation.

Law and society

Several old sayings express the idea that law or ius is a principle or necessary condition of society: ubi societas, ibi ius ("where there is society, there is law", or "without law, no society"), fiat justitia ne pereat mundus ("let there be justice, so that the world will not perish"). It is unfortunate that Latin, and also French and English, have only the word 'society' to express this idea which is, in fact, the fundamental presupposition of natural law. This is unfortunate because, as we shall see below, the ambiguities of 'society' may easily mislead us to read into these old truths a completely mistaken idea of law. However, we can infer the proper interpretation if we recall the original idea of law as laeg, the lay-out or order of things. The opposite of laeg is orlaeg (the old English word for war; it survives in Dutch as 'oorlog'), the desintegration of order (Dutch: 'war'). The modern English 'war', like the French 'guerre', derives from the Frankish 'werra' (disorder, confusion). Thus, society, or the condition of social existence, implies the absence of war and warlike actions that create disorder by destroying social bonds. In Latin, 'ius' stands in opposition to 'iniuria', the general term for typically warlike actions: insults, willfully inflicted injuries, takings of and damages to property, kidnappings,.... Such acts destroy society, or the social bond (objective ius). That they do so is obvious when we consider a society of two persons. On an island with only two inhabitants, there is no society, if they engage in actions that are injurious to the other. In larger settings, such actions continue to produce their destructive effects, although these may not be so immediately obvious or threatening when they leave a large number of social bonds intact.

In the light of these considerations, we may say, that society is the absence of war, i.e. peace, in human relationships. Society is therefore a shared mode of existence without enmity, i.e. a condition of friendly interaction or friendship. Furthermore, the purpose of warlike action, the intention of an enemy, being the destruction or impairment of another's faculties of independent existence or work, war and enmity are direct threats to a person's freedom. It appears therefore, that society is the condition of peace, or amity, or freedom. The conceptual links among "peace", "friendship", and "freedom" should be obvious if we consider that we cannot have one of these things without any of the other two. In some languages, most conspicuously in Dutch and German, this link is suggested even by the form of the words: 'vrede', 'vriendschap', 'vrijheid', and 'Frieden', 'Freundschaft', and 'Freiheit'. Etymologists trace the origin of all these words to the old Indian word 'priya' (one's own) which I have discussed earlier as the root of 'freedom'. There is also nothing mysterious about this logical connection between the concept of property and the concepts of peaceful, friendly and free relations. Friendly relations are peaceful relations, without iniuriae to person or property. Peace is a condition in which people can enjoy their property and independence, without being subjected to hostile treatment. And people are free to the extent that others treat them peacefully and friendly, respect them, their work and their property - in one word, their right (the physical domain of which they are the authors) - by dealing with them according to ius, i.e. by abstaining from iniuriae or warlike action. Thus, the security of each person and his or her property against predatory attack emerges here as the necessary condition or principle of society, its basic law or ius. We see, then, that the definition of law as "society itself", which, as we have noted, lingers on even in some lawyers' textbooks, should not be taken as a mere rhetorical flourish. It reflects an immemorial pattern of thought that has been transmitted in many Indo-European languages, and even today forms the core of liberal views on man and society.

From a natural law perspective, right is id quod iustum est, i.e. what is in accordance with objective ius, or law, or social existence. More specifically, a subjective right is action or activity that is in accordance with the requirements of society, the respect of the person and property of all people. It is in this precise sense that we should understand the ambiguous but popular definition of a right as what is socially acceptable. Unless we understand a right as what is acceptable to "society itself", we lose the connection with objective ius or law. This happens when we interpret the phrase 'socially acceptable' as "what is acceptable to public opinion, or the ruling opinion, the opinion of the rulers, or of some dominant or majority group". Such a subjectivist interpretation sacrifices the objectivity of law on the altar of arrogance ("Law is what is acceptable to us, we are [the source of] the law"). More importantly, it leads us back to a confusion of the lawful and the legal, and into a confusion of two radically distinct concepts of society. As noted already, the latter confusion is all the more likely for speakers of English (or Latin or French), who have only the word 'society' to express both concepts. Speakers of the Dutch language do not have this problem: they can easily distinguish between "een samenleving" (literally: a living-together or symbiosis) and "een maatschappij" (literally: a society or company).

A society-as-symbiosis (samenleving) is not some well-defined, organised group, but precisely that condition of lawful co-existence that we have been discussing all along. It is perhaps best described as the way of life of those who live as free persons among their likes. Thus, society-as-symbiosis is coextensive with objective ius or law. It is a horizontal society without hierarchical structure. It is also an inclusive society without a formal organisation based on certified membership. Anyone who accepts to live according to law is, by that fact alone, in society; anyone who does not is, by that fact alone, an outlaw, i.e one who is outside society. While people in society participate in society, they do not participate in the action of society, because society is not a source of purposive action. It is a general, a-centric society because there is no particular common goal and no central authority that that controls or directs the activities of the rest. Interactions among those in society have the character of meeting, exchanging and parting, or of freely entering into, or exiting from, durable relationships on peaceful, friendly terms. Thus, society-as-symbiosis is a catallactic society. It is inapproriate and misleading to say, that one who is in society is a part of society, or that he is related to society as a part is to a whole. The symbiotic relations among persons are catallactic, not mereological. It is therefore nonsensical to hypostasise society-as-symbiosis, to ascribe some sort of legal or fictional personality to it. No person owns it, and no person is responsible or answerable for it.

A society-as-company (maatschappij, German: Gesellschaft) is a company of mates (Dutch: 'maten', literally: people who share their meat, or eat from the same table, or live from a single common source of income). The mates or members are to be distinguished very clearly from those who are not members and as such have no claim to a share of the income of the company. The Latin societas also is a company of socii (literally: followers, but also mates, compagnons, partners, assistants). 'Societas' and 'socius' are related to the verb 'sequi', to follow. Thus, the constituent relationship of a societas is that of following, or, when it is looked at from the other side, of leading. The leaders lead by imposing their lex, that is to say: by directing the actions of the followers by calling on, or compelling, the followers to do as they are told. A society-as-company is not at all like the general condition of peaceful, friendly and free co-existence. It makes sense to ascribe a fictional personality to it, on account of its hierarchical structure implied by leading and following, commanding and obeying, ruling and being ruled. A company does have leaders, maybe even owners, who can be held responsible and liable for the actions of the whole. In contrast with a society-as-symbiosis, it does have a formal condition of membership, and usually a number of more or less elaborate procedures for admitting new members, determining the status of a member within the organisation, confirming and terminating membership. It is, therefore, an exclusive, vertical society. It is also a mono-centric, particular society. Society-as-company is not a catallactic society, but a mereologically organised whole, with each member playing its prescribed part in the action of the whole. It is coextensive with the actions of its members only, at least in so far as these take part in the action of the company itself.

'Ubi societas, ibi ius' takes on a entirely different meaning if we interpret 'societas' in the exclusive sense, as society-as-company, rather than in the inclusive sense, as society-as-symbiosis. The conditions of existence of an exclusive society or company are very different from those of an inclusive society. They are usually discussed under such headings as loyalty, fairness (or distributive justice) and solidarity: loyalty of the members to the company or its leaders, and of the leaders to the stated goals of the company; the members' perception and appreciation of the fairness of its government or management, and the solidarity of its leaders and members, whether in the strong sense of a willingness to assume responsibility for all the actions of the company or any of its members, or in the weaker sense of a willingness to help other members. None of these factors is to be taken for granted, of course, and it is not surprising that a great deal of effort is spent in trying to figure out how companies can be kept going. The object of this "science of management (or government)" is not essentially related to the study of law, even if the existence of a company is undermined by conflict, internal hostility, and other divisive factors that reduce the company's ability to function as a unit. Society-as-symbiosis, on the other hand, reflects people's ability to go their own way, individually or in the company of others, in freedom, peace and friendship.

The idea of justice as "necessary for society" is therefore ambiguous in exactly the same way as the term 'society' itself. So is the idea of a right as "what is acceptable to society". However, within a particular or exclusive society, justice necessarily is a relativistic notion, whereas justice as the condition of existence of inclusive society is not. There are indeed many societies-companies of different sorts and sizes, with different organisational structures, conditions of membership and statutory purposes. Every particular exclusive society will have its own particular conditions of existence and success; and these serve as the standards for evaluating the justice of its principles of organisation and policy, its leges. On the other hand, society-as-symbiosis always and everywhere implies the fulfilment of the same condition, which is that people abstain from war-like action in their dealings with one another. However, because of their exclusive nature, many separate societies-companies can exist side by side and interact in more or less friendly ways, depending on whether they operate according to law or not. Note that an exclusive society's lawfulness depends in no way on whether it acts in accordance with its own criteria of justice. There is also no reason why a company should meet the requirements of law in order to be succesful in its own pursuits. There have been, and are, many companies that are organised in clear defiance of the principles of law; as well as many companies that are constituted in a lawful manner, yet operate in a warlike fashion. Such organised crime evokes the need for organised defence, maybe even for what is usually called a political organisation. The latter sort of organisation, like any other sort of company, may be organised in a lawful or unlawful manner. However, let it be ever so lawful in all respects, let it be ever so vital for the protection of society-as-symbiosis against predators, its own organisational principle or lex is in no way a determinant of law. And this holds true, even when a company grows really big and powerful enough to defy law with impunity and on a large scale - when it sets itself up as a state. As long as humans remain what they are - separate beings of the same sort, capable of independent action or work - law remains what it is. Moreover, law, which belongs to general society, takes precedence over lex. For unlike general society, companies are mere means of action, and not indispensable to social existence. People can and do move in and out of companies, become members or associates of more than one company; companies can be merged or split up, reorganised, dissolved, and so on - without anyone inflicting any unlawful harm on anyone else or weakening the texture of general society. General society is not a means of action of anyone. It is the condition under which every person can lawfully pursue his own goals, individually or in the company of others. But except for the leaders or organisers, most members of a company are primarily tools to be used and managed in furthering the goals of the company or its leaders.

Concluding remarks

Before drawing conclusions from the analysis presented here, I should recall the main findings. We found that etymology reveals a clear pattern underneath the confused and confusing language of law, rights and justice. On the one hand, "right" is at bottom is not a moral or normative, but a physical notion. It refers to what is under the effective control of a person, what he masters by skill, force or violence, or manipulates at will. The notion of a lex applies when a large number of people are within the right of some other, who can set them to work by a single call or command. On the other hand, "justice" refers back to ius, which does indicate a social or moral bond, a commitment or agreement that originates in solemn speech. Ius can only exist between human persons, while right can exist between a person and anything (including another person) that can be manipulated or controlled by force or the threat of violence. The rational character of a ius presupposes the likeness of those things between which it exists, especially as regards the faculty of speech, the real and organic freedom which are given by their natural (biological, genetic) constitution, and therefore also their mutual independence. These presuppositions regarding the co-existence of physically bounded, mutually independent, rational beings correspond to the condition of objective ius or law, the basic order or lay-out of the world. This order is preserved as long as people exercize their organic freedom within the fixed boundaries of their physical being and the ever-changing boundaries constituted by their work - the two together defining the order of persons and their property. The exercise of power in this specific sense is the concrete manifestation of organic freedom; however, it reveals its lawful character as a subjective right only within the context of objective ius, when it is fitted into the general pattern of freedom among equals.

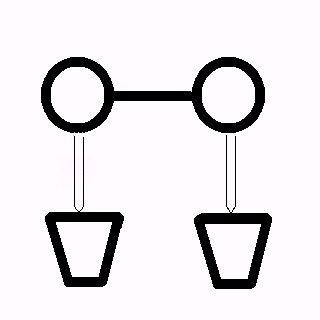

As described here the complexity of the concept of law results from the combination of an inward-looking relationship between a person and his means [of life, action and production, i.e. his property] and an outward-looking relationship between a person and his likes. We can map this complexity diagrammatically as shown in the figure. The diagram represents the basic form of law as it is determined by its subject-matter: the peaceful, friendly and free symbiosis of human beings.

We can use the relationships depicted in the diagram to formulate a pure "logic" of law, as well as the axioms for a formal theory of law. This logic of law is not concerned with norms or directives. It is neither some kind of deontic logic, nor some kind of logic of imperatives. It is instead a logic of just rights. If the formulation of such a logic obviously exceeds the scope of this paper, a few remarks are nevertheless in order. Being purely formal, the logic of law does not by itself force any interpretation of its basic terms ('person', 'means', 'is a means of') upon us. We can, if we wish, treat the diagram above as an empty box and then fill it up in any way we like, using whatever "model" that strikes our fancy. However, under a naturalistic interpretation, one that uses objectively and publicly ascertainable criteria of identification, the logic clearly reveals the pattern of a natural law theory of human rights.

I U S

(law)

-Person A Ü (speech) Þ Person B

ß ( iura ) ß

right right

auctoritas auctoritas

autonomy autonomy

ß ßMeans of A Means of B

The most interesting conclusion we can draw from the preceding analysis is, that "law" is not an essentially normative concept, no more than "right". Law is not a presciption telling us, how we ought to behave. Law is a natural fact, and law is natural law and nothing else. It describes the order of the world - the basic lay-out of human affairs. We do not need any teleological or theological or otherwise metaphysical "knowledge" in order to be able to judge whether some action or relationship is lawful or not. To make such a judgement, we should not focus on what people ought to do according to some "moral" or "legal code", but on the objective or agreed on boundaries among persons. The interesting questions are strictly factual: Who did what, when, how, and to whom? Who made or acquired this? How did she make or acquire it, alone or with the help of others? Did the others consent to help? Did they consent to help only if some conditions were granted? Were these conditions honored? The common presupposition of all of these questions is, that every person is a finite, bounded being, separate from others not only in his being but also in his actions and work or auctoritas. Of course there may be all sorts of complications and uncertainties when we try to answer these questions with respect to particular cases or situations of an unfamiliar type. There is need for efficient and effective ways of dealing with these. This is precisely the area where the expertise of lawyers and jurists is so valuable. However, as it is clear what the questions are and aim at, there is a definite standard by which we can judge any proposed answers or methods for answering them. From this point of view, the objective of the practice of law is to determine and safeguard the law and the just rights of persons in situations where these may be unclear or contested. In this sense, the practice of law is a rational discipline of justice, not of legality.

For the layperson, who gives little thought to all but a few cases where determining rights is problematic, it may be difficult to grasp the point of much of what lawyers practise. However, just as one need not have the knowledge of an architect to know what a house is, one need not know the lawyer's business to know what is law or ius. The knowledge of law requires no more than an ability to grasp the idea of freedom among equals, the ability to recognise others as one's likes, i.e. at the same time, their likeness and their otherness. That knowledge consists in the recognition of the difference between what one is or does oneself and what one's likes are or do. This ability is, from a psychological, even biological, point of view, so vital, and at the same time, from a sociological point of view, so fundamental for the existence of social order, that we simply expect any person to possess it. Nemo ius ignorare censitur: nobody should be thought to ignore the law. While this old maxim makes no sense whatsoever when we take ius or law either as the specialised skills of lawyers or as the output of legislation and regulation by governments, it makes eminent sense when we take law or [objective] ius as the condition that makes society possible: the recognition of the separateness and likeness of persons. When it is applied to legal systems - and it often is - the maxim merely expresses the arrogance of rulers who assume that everybody else carefully takes note of, and obeys, their commands, or else turns for advice to those who specialise in listening to the rulers (lawyers, not as experts in iustitia, but as experts in the current state of legislation).

The modern intellectual is not likely to give up her objection to natural law merely on account of the fact that it has nothing to to with a metaphysical "higher law", and everything with the order of persons and their property rights. With an obligatory reference to Hume, she will insist that one cannot logically infer a norm from a fact. Therefore, if natural law is given a naturalistic interpretation nothing follows from it regarding what we ought to do. In other words: even if natural law should tell us how things are, it cannot tell us why they should not be different; it is no basis for criticism of human actions in general, nor, in particular, of legislative, judicial or administrative rule- or decision-making. However, Hume also expressly noted that it is not improper to call the rules of justice Laws of Nature "if by natural we understand ... what is inseparable from the species". Hume's remark about the gap between is and ought was meant to "subvert all the vulgar systems of morality", not to condone action in defiance of what is inseparable from human nature. For Hume, justice is "an invention [that] is obvious and absolutely necessary; it may as properly be said to be natural as any thing that proceeds immediately from original principles, without the intervention of thought or reflection." Justice is not something inevitable or unavoidable, but it is indispensable, the world and the human species being what they are. Why, then, should we act within the bounds of justice? Not because we cannot do otherwise, but because so much depends on it. Our intellectual may then cynically object, that there is no proof that she ought to care about the things that depend on natural justice. There is no direct reply to this objection other than a proof of the thesis, that we ought to be just. If our intellectual only argues, that there is no reason for believing that aggression or warlike action is "unjust", she is plainly mistaken. To bring another within one's "right" by warlike means is just as obviously a violation of the conditions of ius as defence against injurious attack is a just subjective right. Democritus said it well: "It is needful to kill the enemy, whether a wild or creeping thing or a human being."

References

Aquinas, Th. (ST) Summa Theologica.

Aristotle (NE) Nicomachaean Ethics.

Aristotle (PO) Politics

Chafuen, A. (1986) Christians for Freedom: Late-Scholastic Economics, San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Christman, J. (1994) The Myth of Property: Toward an Egalitarian Theory of Ownership, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Diels, H. & W. Kranz (1952) Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Berlin, 10th edition.

Flückiger, F. (1954) Geschichte des Naturrechts, Erster Band: Altertum und Frühmittelalter, Zürich: Evangelisher Verlag

Hart, H.L.A. (1961) The Concept of Law, Oxford: Clarendon Press. New edition, 1994

Havelock, E.A. (1957) The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics, Yale University Press.

Hayek, F.A. (1960) The Constitution of Liberty, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Hayek, F.A. (1967) "The Legal and Political Philosophy of David Hume", in F.A. Hayek, Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Hayek, F.A. (1973) Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume I, London: Routlegde & Kegan Paul.

Hayek, F.A. (1978) "The Confusion of Language in Political Thought" in F.A. Hayek, New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and The History of Ideas, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hayek, F.A. (1988) The Fatal Conceit, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hobbes, Th. (1652) Leviathan.

Hoppe, H.-H. (1989) A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hume, D. (1740) A Treatise of Human Nature.

Kelsen, H. (1960) Reine Rechtslehre, 2nd Edition, Vienna 1960.

Locke, J. (1690) Second Treatise of Government

Lomasky, L. (1987) Persons, Rights, and The Moral Community, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Popper, K.R. (1945) The Open Society and Its Enemies, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1945, many editions, some with revisions and addenda.

Ross, A. (1958) On Law and Justice, London: Stevens and Sons.

Rothbard, M.N. (1995) Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Edgar Elgar.

Rousseau, J.-J. (1762) Du Contrat Social.

Tuck, R. (1979) Natural Rights Theories: Their Origin and Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tuck, R. (1994) Philosophy and Government, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Van Apeldoorn (1985) Inleiding tot het Nederlandse Recht, Zwolle, 18th edition

Van Dun, F. (1983) Het Fundamenteel Rechtsbeginsel ("The Fundamental Principle of Law"), Antwerpen: Kluwer-Rechtswetenschappen

Van Dun, F. (1986) "A Formal Theory of Rights", Working Paper, Vakgroep Metajuridica, Faculty of Law, University of Limburg, Maastricht.

Van Dun, F. (1986b) "Economics and The Limits of Value-Free Science", Reason Papers, n° 11, 17-32

Van Dun, F. (1996) "Philosophical Statism and The Illusions of Citizenship: Reflections on the Neutral State" (forthcoming in Philosophica)